Exchange Ships: A Paradigm in Global Diplomacy

Swiss Diplomacy of «Good Offices» in Asia during World War II

In diplomatic history, the so called «good offices’ diplomacy» is a well-known but still under-investigated characteristic instrument of Swiss diplomacy. Historiography usually understands practices of mediation as related to cases of emergency. Most notably, they are utilized when diplomatic relations have ended under the conditions of war. From such a moment onward, war parties depend on the mediation of a neutral third party when bilateral questions arise which require some form of negotiations. This approach is useful for understanding intergovernmental communication during wars. However, this project uses the practices of Swiss mediation in Asia during World War II in a different way: it argues that the practice of «good offices» serves as an analytical lens to elucidate the development and impact of global expertise. Following this approach, we emphasize that Swiss mediation presented an opportunity to overstep formal bilateral conversations between warring parties based on normative diplomatic rules.

This approach creates three newly shaped research perspectives:

Most of the Swiss diplomatic representatives were local residents. Therefore, they were part of the community of foreigners who came under pressure during Japanese occupation. Through the eyes of the Swiss representatives, the complex networks of fugitives, foreigners, prisoners, and allies in its various forms of (dis)entanglement gain visibility in global history. At the end of World War II, Switzerland had become the representative of an immense variety of states on a global scale. The transformation of these multi-layered networks from documenting colonialism into forced migration under the condition of war allows to critically ask about concepts of transculturality and transformations of colonial societies.

The Swiss practice of «good offices» appears as consequence of an early industrialized and export-oriented society. The early presence of Swiss in Asia left their imprints in form of a specific understanding of global presence, demands of markets, and expertise, documenting global opportunities of small and neutral states in the wake of great powers. In this research project, this approach is discussed with the metaphor of Switzerland as a «global nation».

We argue that the new reading of the Swiss «good offices» unfolds hidden parts of the global history of World War II. One of the most spectacular but little-known activities during the war in the Pacific gets into view: the exchange of «enemy nationals» through neutral ships. These exchange activities offer a crucial and new understanding of the question to what extent the multiple layers of globality shaped the theatre of war with long lasting consequences for the postwar period.

Exchange operations

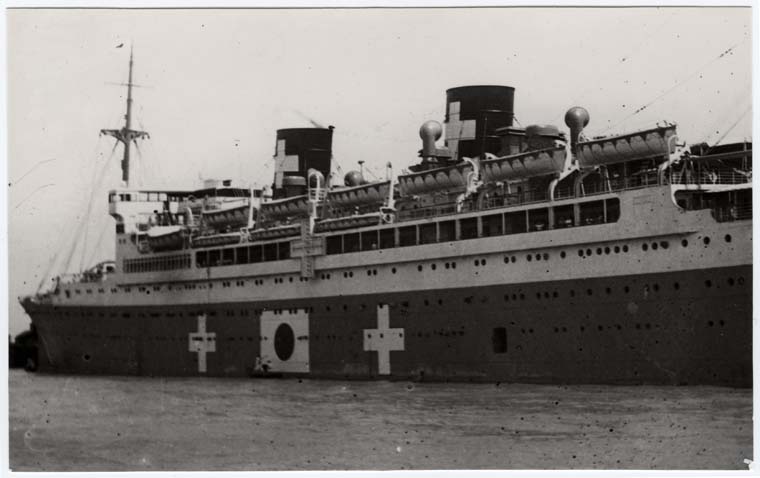

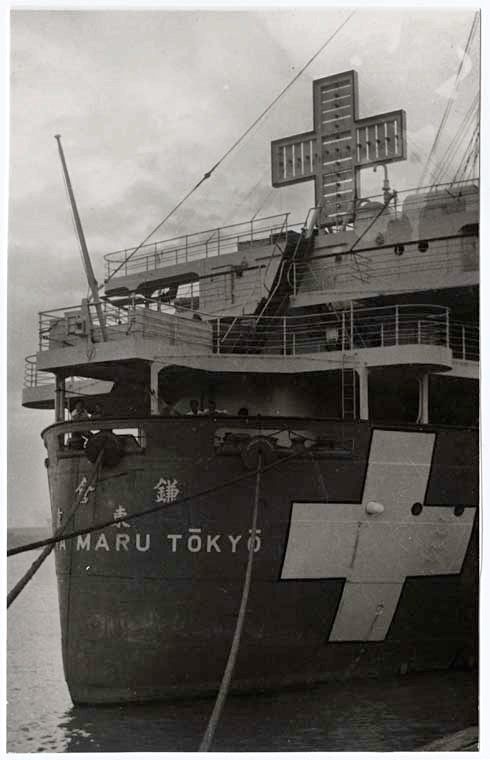

During World War II, the warring parties imprisoned civilians whom they declared as «enemy nationals» in internment camps in Asia, Europe, and the US. From 1942 onwards, a number of complex agreements between the warring parties resulted in activities of «repatriation».. Such activities aimed to include diplomatic personnel, but mainly civilians. Some of them had lived over years in places which now were called «abroad» in reference to their nationality, although the expressions «enemy alien» and «repatriation» did not correspond to the people’s self-understanding. In many cases, the «repatriation» was an act of forced migration. It took place on ships which were especially chartered for this purpose. Marked with the emblem of the ICRC and sometimes even more explicitly with the word «diplomat» at the long side, the ships started in American, British and Asian ports and travelled for the so-called exchange to Portuguese neutral ports in Goa or Mozambique. A Swiss representative was always on board, observing the negotiated conditions of exchange – e.g. the checking of passengers’ lists, the handling of luggage, freight, and money. Since the Swiss delegates received all information from both sides, the source material available in Swiss Archives allows a unique view into one of the most spectacular, but under-investigated operations the Pacific War had to offer.

Ships as neutral space: The example of the Teia Maru

© ICRC. Rapatriement des ressortissants américains sur «Teia Maru», navire japonais de 15'000 tonnes (Shanghai).

The ships hired by the governments for exchange operations had served as luxury liners in the upcoming cruise business before World War II. The ships offered a passenger capacity between 600 to more than 2000 passengers. Some of these ocean liners gained a metaphoric value as repatriation ships – e.g. the Swedish MS Gripsholm. The Japanese ship Teia Maru stands for a less known, complex historical background. The ship served as exchange ship in 1943 and was sunk by an US submarine in 1944. Originally, the ship was a French Cruiser, sailing under the name of MS Aramis. The ship was converted into an armed commercial ship and seized in Vietnam by the Japanese forces. Renamed as Teia Maru, the ship with unusually shaped chimneys served as exchange ship in 1943. In October of the same year, the ship arrived the Portuguese port of Mormugao in the neighborhood of Goa to meet the MS Gripsholm, coming from the Americas. The exchange of the passengers filled the Asian and the Western newspapers, both eager to quote the latest news from the respective theaters of war. Photographs of this ship with an illuminated Red Cross at the top circulated globally thorough Western and Asian media.

Swiss diplomacy: The making of a global nation

During World War II, exchange operations involved a considerable number of agencies. The coordination of these multiple actors transformed the «good offices» into a tool that went beyond the diplomatic services offered by neutral states. In the Swiss case, the exchange operations connected diplomatic services with relief activities of the ICRC. In addition, exchange ships addressed the limits and grey zones of the contemporary rules of international law in a paradigmatic way. On board of the ships, the representatives of a civil society intertwined with diplomatic personnel, from military attachés to consular staff. The spheres of activity, carefully separated by diplomatic rules until now, constantly overlapped. . Both sides of the warring parties brought their attention to the categorization of the passengers of the ships. All these categories, however, overlapped: On the one hand, the category of diplomatic personnel would encompass the Chinese gardeners and cooks. On the other hand, the civilians raised suspicions just because of their profession or knowledge, for instance when they provided expertise of possible military use. Therefore, the warring parties tried to avoid that passengers on exchange ships turned into sources of information about the enemy country they had left. At the same time, both axis and allied powers established meticulous interrogations of their own «returning» citizens to gain information of military relevance. In this highly nervous and volatile atmosphere, the expectations towards the «good offices» went far beyond the usual representation of enemy states. Instead of bilateral operations, Swiss representatives worked on a global level. Exchange ships stopped in almost every port with foreign residences within the Japanese occupied territories. The community on board therefore mirrored almost every sort of broken, redirected, and destroyed biography and exemplified the dark side of the twentieth century.

In this social context, the European theatre of war was equally present in the Pacific: Exchange ships hosted diplomats representing one of the many exile governments in London. The Swiss representative hoped for a quick stay in Vietnam ruled by Vichy France, since representatives of De Gaulle’s Free France movement came on board. Jewish families struggled with passport issues. The same did the many individuals stranded in Shanghai after a long journey from Western Europe through Siberia or from Syria and Egypt. American missionaries from China met with Latin American representatives from Manchukuo and Korea. The Swiss representatives on board guaranteed for the correctness of the passengers’ list, and had to persuade the diplomatic representatives to give their cameras and papers in the Swiss custody. In addition, many of the passengers needed financial support. The many small sums paid to passengers were part of an extended and complex global flow of money whose administration by Swiss representatives touched questions of crucial relevance such as the ratio between US dollar and the value of «military yen» introduced by force in the occupied territories.

The reconstruction of exchange operations sheds light on a missing part in the history of the Pacific War and the role of Switzerland, and thereby contributes to new perspectives on a global history of World War II. In addition, through the lens of activities of good offices’, the Swiss practices of mediation provides insights into the development of global expertise within a small export oriented country with a rather small diplomatic apparatus. This ongoing research project will therefore fleshing out the specific personnel and structural background within the Swiss system. Our investigations explore, for the first time, how the specific use of transcultural expertise gained by long lasting commercial contacts shaped and developed the Swiss characteristic as a global nation.

Prof. Dr. Madeleine Herren-Oesch